I was just in San Diego doing some private training with a client that included night shooting each evening. One of these evenings, I was detained by military police for about 30 minutes while making photographs on a public sidewalk. On this particular night we were apparently near, but not on, a naval base. It was 2am, and I had my tripod setup under a streetlight. I was enjoying the playful, intermingling colors from neighboring mercury vapor, metal halide and incandescent light along this particular street. I was making images of the streetlights and of the streets themselves, not of the naval base or its industrial gate entrance down the street. Here’s the image I was making when a hummer full of soldiers in camouflage pulled up and said “Hey – what are you doing? Don’t move!”

I love telling people what I’m doing when I’m shooting and night, and often show images to explain the concept of making this kind of art. But these guys didn’t want to see my images; they called for backup. As we waited for a few more vehicles of military police to show up, I was told not to move. I knew I hadn’t done anything wrong, and that I really didn’t have anything to worry about, except for my friends who were a hundred feet away around a corner. When 2 more vehicles of solders showed up, things got more heightened. The new arrivals questioned the first solders about me and several were simultaneously talking on walkie talkies. “What kind of pictures are they?” “Did he get the ships?” “Who does he work for?” “What does he look like?” etc etc. Obviously, this “what does he look like?” questions implies that looking a certain way is also suspect. For the record, I’m an average-sized, 37 year old male with short dark hair. That night I was wearing cargo pants and a button-down shirt. By the time they actually decided to talk to me, I have to admit I was struggling to keep a worry free attitude. Being surrounded by military police vehicles with flashing lights and lots of well armed solders in camo and not being allowed to move can be intimidating.

I’m used to getting stopped by police and Border Patrol for making images at night. Working with photography at night is a foreign concept to most people, but easily overcome. In situations like these I don’t panic. Instead I show my enthusiasm for the creative process I’m involved in. I respect their authority, show them example images on my phone, move if they ask me to and express genuine appreciation for them keeping an eye out for us. I also know that US citizens have a right to photograph in any public space in America. People can even take photos of private property, military bases, police on duty, etc, as long as it’s done from a public space. Photographers can’t trespass and should always be respectful of other people and their property while making images. Again, my tripod and I were set up on a sidewalk, a public space.

Gesturing with his hands in one direction and then another the head MP says to me “your talking pictures… and it smells like terrorism!” He says it again, this time slowly with greater emphasis: “your talking pictures… and it smells like terrorism!” He says it one more time, in classic loud, drill sergeant style followed by “Ya see?”

“OK,” I say, “Can I show you the image I was just making?”

“No, no, no” he says and goes on and on about how important this navel base is and how there are lots of ships here. “And believe me, there ARE terrorists in this area!!” he says loudly while making a circling gestures over our heads

Rule number six on the Photographer Rights Card includes this line “Photographing from a public place cannot infringe on trade secrets, nor is it terrorist activity.” What I wanted to say to this soldier was “I’m on public sidewalk under a bright streetlight and can legally make whatever images I like from here, including those of the navel base you’ve just informed me about. If I was a terrorist I probably wouldn’t be so obvious – I’d probably shoot from a car across the street wouldn’t I?” But I didn’t say these things. No need to question their authority. No need to increase my chances fog being detained any further. And that’s what I was worried about at the point – that I might get pushed into a vehicle and taken somewhere for further questioning. Perhaps they would label me as a potential enemy combatant and deny my civil liberties. That might sound extreme, but this possibility was starting to seem very, very real. I overheard the words “confiscate” and “take him” on the walkie talkies as I talked with the soldier. I didn’t want to reveal that I was out with other photographers that were just a hundred feet away, let alone leave them behind when I had the keys to the car.

The officer wanted to know my name and where I lived. Now, what would you do in this situation? Would you willingly do whatever they say or demand that your civil liberties be honored? I was so nervous that I couldn’t even remember that I didn’t have to answer such questions. I told them my name, and where I was from. I told them that I show my work in galleries, and that my images sometimes take hours to make, and often involve painting with light from flashlights. “Come on, let me show you the images I’ve been making tonight.” I said. He initially declined, but curiosity got the best of him. One look at the image above and the others I had made that night and his relief was obvious and his tone went from drill sergeant to buddy. “Awww, so you aren’t taken pictures of tha ships, or tha entrance or nothing are you? Well that’s real interestin’ You’re an arteeast! ” We shook hands and I was glad to walk away and check in with my night photography buddies who, despite all the flashing lights had missed the whole ordeal. “We would have gotten detained in solidarity with you!” they joked. It was nice to feel free, and be with friends.

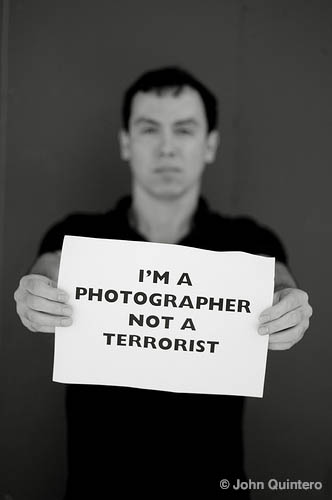

Unnecessary harassment is getting more and attention in the press lately as our post 9-11 world seems to be getting even more on edge when it comes to citizens with cameras. Things have become so heightened that there are recent stories where police assault harmless, ordinary people with cameras, arrest them and charge them with assaulting a police officer. Police have been known to simply steal cameras out of civilian’s hands and deny the camera ever existed later. In the UK, section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000, actually gives police the right to detain and search anyone upon suspicion and seize anything considered to be in connection to terrorism. In the UK, the I’m a Photographer, not a Terrorist campaign has successfully suspended section 44 while it’s under further investigation. In the US, police and citizens alike have always had the right to take pictures in public. Recent events suggest that more dialog and increased awareness might be in order.

Unnecessary harassment is getting more and attention in the press lately as our post 9-11 world seems to be getting even more on edge when it comes to citizens with cameras. Things have become so heightened that there are recent stories where police assault harmless, ordinary people with cameras, arrest them and charge them with assaulting a police officer. Police have been known to simply steal cameras out of civilian’s hands and deny the camera ever existed later. In the UK, section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000, actually gives police the right to detain and search anyone upon suspicion and seize anything considered to be in connection to terrorism. In the UK, the I’m a Photographer, not a Terrorist campaign has successfully suspended section 44 while it’s under further investigation. In the US, police and citizens alike have always had the right to take pictures in public. Recent events suggest that more dialog and increased awareness might be in order.

How to deal with the authorities when photographing at night is a regular topic that Lance Keimig and I talk about during our night photography workshops and is discussed Lance’s new book. In my opinion, these situations are like any other confrontation. Don’t let the situation get heightened. Don’t be disrespectful or threatening in any way – even in the most slight, psychological way. Don't demand that your rights be respected. Don’t assume that they will respect your rights, either. Be patient and try not to get offended. They are doing their job and may not be trained as well as they should be. Be patient. These situations can be scary and people act differently when they are scared. If you can control your reaction you’ll probably control the outcome.

I have conflicting feelings about my experience. I’m glad they didn’t automatically assume I wasn’t a tourist, but I wonder what my experience would have been like if I had a full beard, or was wearing a hoodie. I’m glad they are keeping an eye out for suspicious activity. I do think security and civil liberties can co-exist. And a helping of sanity, patience and friendly communication can go a long way.